Our first stop in Beckley was the Exhibition Coal Mine, which includes admission to the Youth Museum. We drove into a mini-town (still in the center of Beckley) with buildings – a church, house, etc. It was almost hard to find the museum to enter. Once inside we purchased tickets for the coal mine tour. Departing every 30 minutes, we had 25 minutes to explore the museum upstairs.

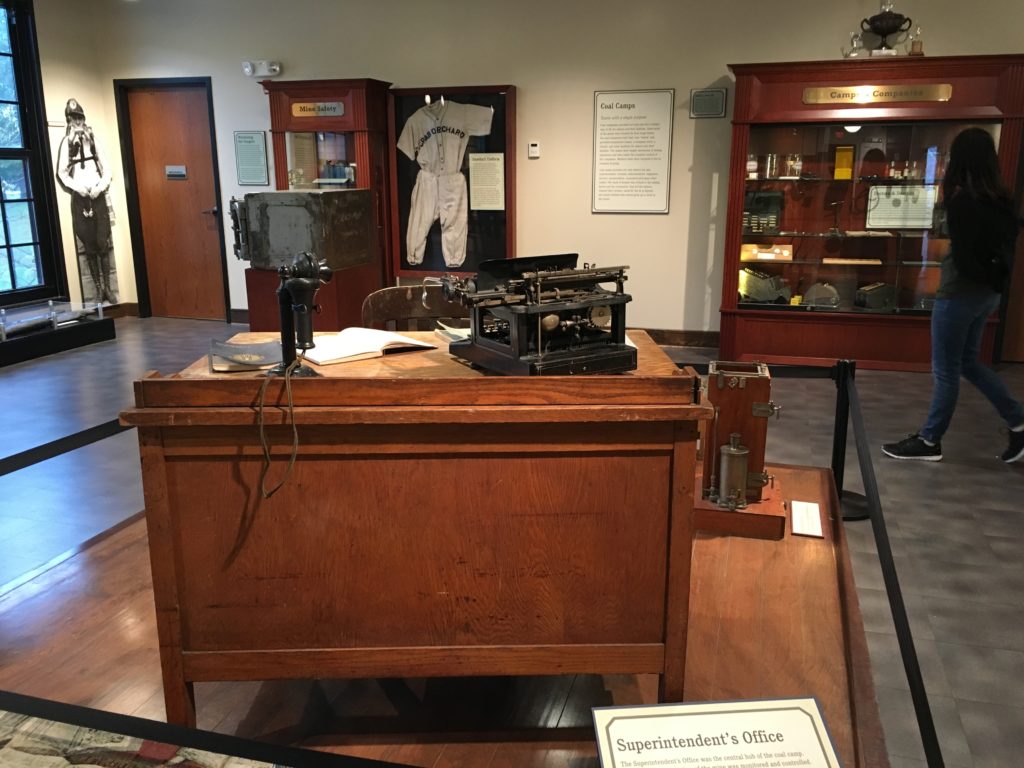

At the top of the stairs, wide rectangular, black and white photos of entire coalworkers greeted us. Along the walls, montages displayed various themes with a placard explaining the items. One was rudimentary medical instruments used by the doctors – even if you didn’t need a doctor, the item was deducted from the miner’s paycheck – lunch pails – which were metal and had three horizontal compartments – the bottom was for water, then the food and on top was for pie/dessert. I guess you’d need pie every day to deal with those working conditions. Another montage showed tools – one with a tool you hooked on to your stomach to drill and a picture of a miner using it. Another display case showed miner’s id tags that were used to show who was in the mine.

The curator announced the “boarding call” so we walked outside to the depot where we sat on two – open air trolley trains. Leroy announced, “Ready for work?” The older, skinny man was a former miner and his father had been too. He drove us in into the black tunnel lit every few feet with electric lighting. I thought we’d go down, but instead we were horizontally inside the mountain.

At the first stop, Leroy stepped out and showed us the “Supply Station” where miners would load mules before the trolley system. “Remember you don’t get paid for rock,” he said. Only coal counted in how much a miner was paid at the end of the day.

He passed around a small metal object that resembled Aladdin’s lamp. A miner would fill it with kerosine (purchased from the company store) and it would give him about an hour’s worth of light. Leroy turned off the electric lights and showed us how little light the miners had. The miner would attach it to the top of his cloth cap as it was before hard hats.

Later, cetaline was used which gave the miner about 4 hours of light. Passing it around for us to smell, it reminded me of methane gas so the tunnel obviously didn’t smell great back in the day. To light it, Leroy had to deprive it of oxygen, sticking it and putting his palm over the opening. Leroy showed us a small canary cage. Miner’s would buy a canary and take it with them to the mines. They’d set it down on the floor. If the canary died, that meant oxygen was being deprived and they had to get out of there quick – or they’d succuumb to black damp. At one time, they used roosters or chickens but their lungs lasted longer than a human’s.

At the next stop, we saw a large coal wagon. On a good day, a miner would fill 4 of these by hand, by himself to earn about $1.28. Today they’d get about $25/hour. The miner would throw one of his id tags at the bottom (so someone couldn’t switch it out) so he’d get credit for the load. At the top, a person would weigh it and also determine if there was any rock (remember you don’t get paid for rock). A visitor commented that if the person doing the weighing had a grudge against you, they could “miscalculate” your pay for the day. Yes they could.

We moved on and then Leroy backed us into another section where the display was located on the other side. This was the tool area where we saw the original drilling tool like in the museum and then the automated machines used later. He told us that miner’s would work in one place for about a month before the boss moved them to another spot. They’d let the coal become the column for a while and then put in the wood post to hold it up. As automation began, they (by law) had to insert metal rods every 4 feet. Each day, they’d have to test a bolt hole. If it was wobbly, it meant they weren’t in real rock, so they’d have to get a longer bolt to support the mine. You’d have to leave the test hole open for inspectors.![]()

Some of the mines went 7 miles deep and it could take an hour on an 11 person tram to get to your spot. He and his buddies be paid from the time they went into the mine (even though they weren’t at their place) to when they got out of the mine. It wasn’t that way in the begining. Leroy and his buddies would sleep for an hour going and hour going back – while getting paid. He said the companies wisened up to this lost time and would build a huge elevator in the middle to reduce it to 10 minutes or so travel time.

At the next stop, we saw the metal lunch pails. The most important thing was the water. It was all you had for the day.

The track circled back to the depot and we got out after the 40 minute tour. The next stop was the self guided tours through the houses. Docents stationed inside told us about the living conditions. We passed a bachelor’s shanty, which was tiny and rented for $2/month. Then we went inside the supervisor’s house – two story and nice. Not big mind you, but had four or five bedrooms and a bathroom upstairs. After seeing the bedroom and kids room, the other rooms were set up as a barber shop, doctor’s office and mail room just to show you what they would have resembled.

Next we toured the school house which was bigger than I expected. It had one large room that could be divided into two rooms. One was set up with desks, teacher’s desk, dunce cap, chalkboard and books. Along the other walls were film strip projectors, old text books and things I remember from my school days. This schoolhouse had been moved from Helen Coal mine camp. Here was a picture of school chidren in 1948 and they graduated in 1953. Various pictures of school reunions showed the same individuals through 2003. A guide explained the injustice of the dunce system.

Outside we walked through the rain to the miner’s house. The docent said it had three rooms – kitchen, parlor and one bedroom. The bathrooms were the outhouse. Many miner’s rented a room to bachelors as the rent was $6/month. She showed us a miner’s 1937 monthly wage statement. He was paid 66 cents/ton of coal and made $74 dollars. Yet after expenses, including a loan for $46, $2.50 fee for coal to keep house warm (much higher charge than what he was paid for), funeral fund, doctor fee, union fees, company store expenses, he earned only $1.68. “A miner with a family couldn’t get away. Sometimes, a bachelor could, but not often,” the docent told us.

We bypassed the youth museum which had interactive exhibits since we were running short on time and I felt we’d aged out of it. Instead we went behind it (included in tour) to see the Homestead. These buildings (which had been moved piece by piece from various parts of the state) resembled an 1830’s farm. A guide walked us around showing us – the schoolhouse where the schooteacher lived upstairs. We saw the slate where they’d write on.

Next we passed the barn which only housed chickens (and smaller than I thought), the home which looked big on the outside – 2 story, but once inside it reminded me of Little House on the prairie. One large room with big kitchen and table and one bedroom, upstairs would be two bedrooms. At one time 17 people lived in this house, but he didn’t know how many were children. The fire in fireplace would go on day and night – “keep the home fires burning” so they could stay warm and cook. Even had a fire going in the summer for cooking. We passed by the outhouse where people used corn cobs in a bucket to wipe. Yuck! We saw the blacksmith shop which was where the men hung out. Women didn’t go there unless she was a blacksmith. Surprisingly 1 out of 10 blacksmiths were women – usually widow or daughter of blacksmiht that had to earn a living.

I loved seeing the general store. A checkers board was int he middle of the room. Behind the counter was a radio to recieve telegrams? A popular item to buy was canning lids as I guess people preserved food. The store sold fabric too. “Anything you’d need,” said our male guide. Next door was a children’s playhouse that had orginially been a parade float celebrating hte 100 year anniversary of Beckley. It was donated to the Homestead since it matched the decor.

For more informaiton, visit the website at Beckley Exhibition Coal Mine.