Standing tall at 165 feet, the iconic St. Augustine Lighthouse, with its black and white diagonal bands greets visitors to the St. Augustine area. The lighthouse lies just across the Bridge of Lions on Anastasia Island near the beach and is open for tours. While visitors can book specialized guided tours, including sunset and ghost tours, we opted to see the museum and grounds on a self-guided basis.

The Early Lighthouse

Founded by the Spanish in 1565, St. Augustine serves as the oldest European-settled community in the United States. Shortly thereafter, the settlers erected wooden watchtowers along the coastline for protection. By the 1700s, the Spanish replaced many of the wooden structures with coquina stone. In fact, the last coquina-built watchtower still stands at Fort Matanzas.

After acquiring St. Augustine in 1821, the US government attempted to use the watchtower as a lighthouse. For $5,000, the retrofitted lighthouse stood at 30 feet with ten oil lamps.

Over the years, the government increased the height to 50 feet and added a fourth-order Fresnel lens. Soon it was apparent that a taller structure, built out of more sturdy materials and on more solid ground, was needed. It’s a good thing they built the new lighthouse on more solid ground. In 1880, the original watchtower/lighthouse plunged into the ocean due to erosion!

The Current St. Augustine Lighthouse

At a cost of around $100,000, the current lighthouse became operational in 1874. We climbed over 200 iron stairs to the very top. Along the way, eight landings offered places to stop and read historical facts.

One landing in particular featured facts and an early photo of William Russell, the first lightkeeper of the current lighthouse. Visitors could also try to lift the 20-pound barrel of oil nearby simulating what the lightkeepers had to haul upstairs several times each night.

At the top, panoramic views made the trip up the stairs worth it as Matanzas Bay stretched out below. Inside, we viewed the first-order Fresnel lens that still shines its light today. Ordered from France, the lens takes nine minutes to fully rotate and blinks every thirty seconds.

Back downstairs, we passed by the keeper’s office and oil storage room. Lard oil (and later kerosine) powered the light until 1936. Around this same time, an electric motor replaced the hand-wound clockwork mechanism to rotate the lens.

Lightkeepers’ House

Lightkeepers had a tough job – and they needed a place to live. In 1875, the United States built a duplex-style keepers’ house a few steps from the new lighthouse. Working in three 8-hour shifts each, the lighthouse staff consisted of a head keeper, as well as a first and second keeper.

To accommodate the keepers’ families, the north side housed the head keeper and his family while the south side accommodated the first keeper and his family. The second keeper, usually a single male, lived in a room upstairs between the duplex walls.

William Harn, his wife, and five daughters were the first family to live in the new lighthouse from 1875-1889. We entered the sitting room made to look much like it would during the Harn family’s tenure. Each side of the duplex featured two rooms on the first floor, an outdoor kitchen, and two upstairs bedrooms. Harn was paid an annual salary of $720. After his death from tuberculosis, Harn’s widow briefly became a second assistant keeper at a $400 annual salary.

Another exhibit inside the lightkeeper’s house included Wrecked! with artifacts found from a British shipwreck in 1782. Archealogists who discovered the ship in 2009, believe the boat left Charleston to transport many British Loyalists to Florida. During the Revolutionary War, Florida was still British-owned and thus, a safe place for the refugees.

Incidentally, the British gave Florida to Spain in 1784 as part of the Treaty of Versailles. The United States didn’t aquire Florida until decades later in 1821.

Other Buildings and Exhibits

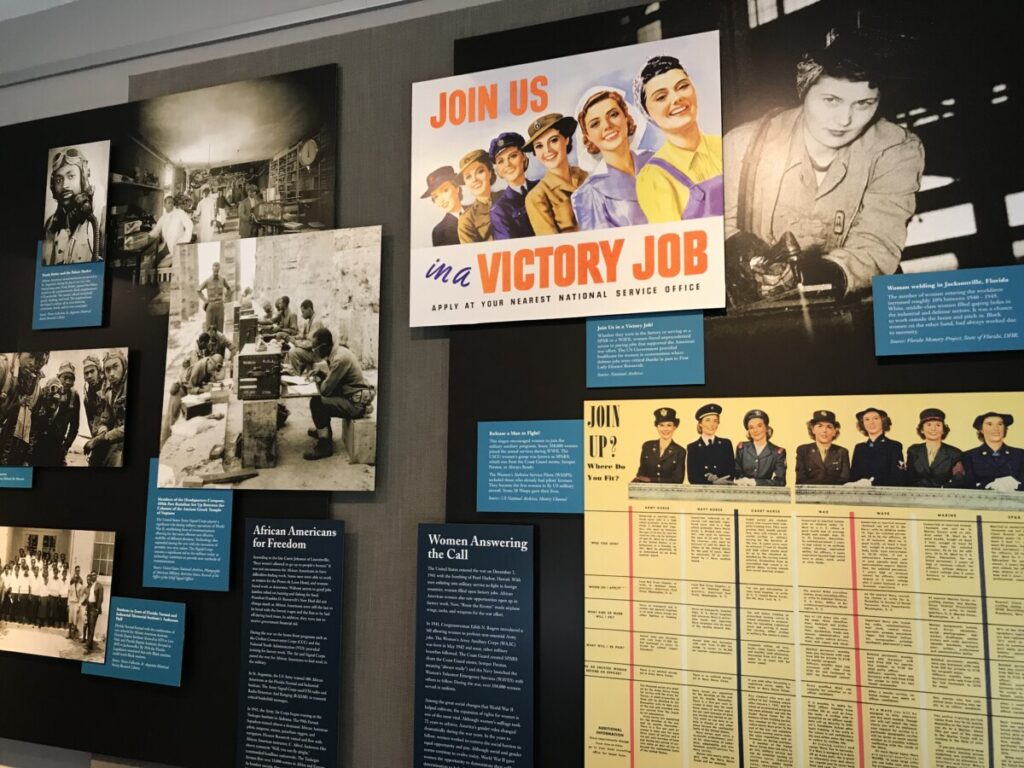

For centuries, the lighthouse provided protection from enemy attacks and World War II was no different. The Coast Guard set up a training center in St. Augustine in 1942, taking over Henry Flagler’s Ponce de Leon Hotel. On the lighthouse grounds, the USCG built a lookout dwelling and a maintenance shed for jeeps used for beach patrol.

Inside the lookout building, the museum presented Guardians of the First Coast. With pictures, letters, a timeline, and other artifacts, we could see the effects of WWII on the area.

As we walked between the buildings, we passed Heritage Boatworks where dedicated volunteers create wooden boats. Past projects include a replica of a 1760 British Yawl, a Florida skipjack, and a Barca Chata (flatboat). An adjacent building housed model ships.

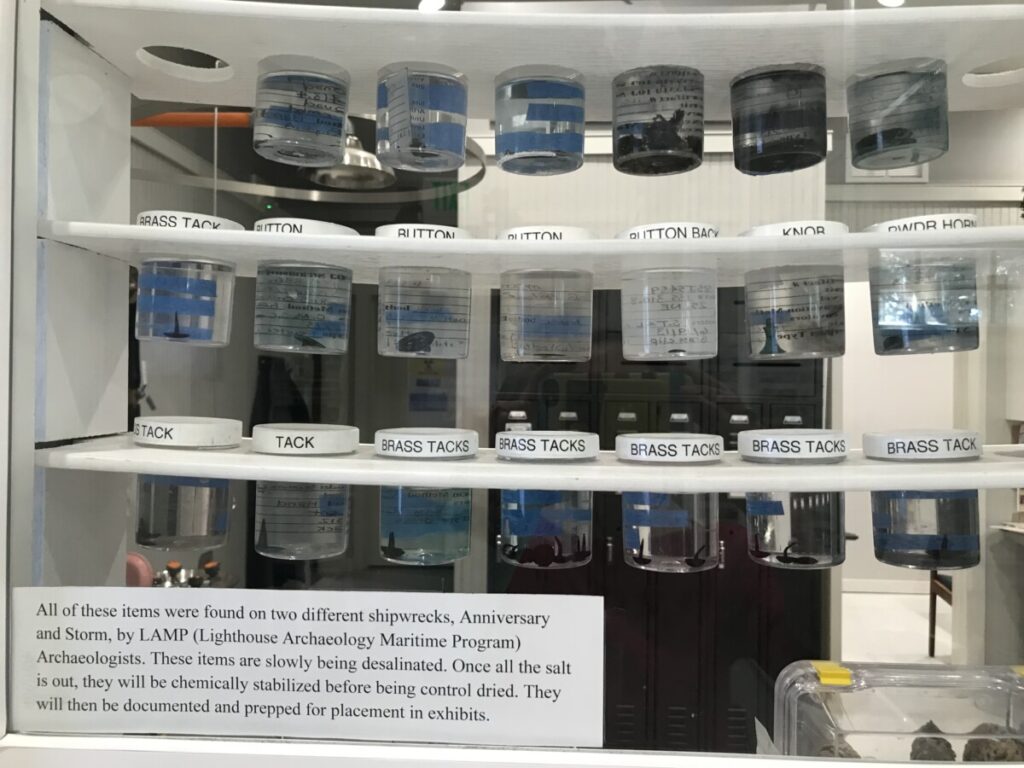

The Conservation Lab highlighted efforts of the Lighthouse Archeaological Martitime Program (LAMP). Founded in 1999, the team conducts maritime research including multiple shipwrecks in the area. Once objects are found, LAMP undertakes detailed work to restore the items to the original condition.

The Lighthouse Today

Once electricity came to the lighthouse, the need for staff dwindled. By 1955, the lighthouse keeper position was completely eliminated. However, a lamplighter visited the lighthouse daily until 1968. With the keepers’ house uninhabited, a fire broke out in 1970. At this point, the Junior Service League undertook efforts to restore the keepers’ house and preserve the area. The museum opened in 1988 and the lighthouse opened to the public in 1994.

For more information about St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum, visit the website here.