At the conclusion of our trip to the Finger Lakes in New York, we found ourselves in Washington, DC. The National Museum of African-American History and Culture (NMAAHC) topped our list of things to see on this trip.

Admission is free but timed-entry tickets are required. Even though the website showed tickets weren’t available on the weekend of our visit, NMAAHC releases a batch of same-day tickets at 8:15 am. It was worth a shot and we secured tickets for 2:30 pm that same day.

A few years ago, I toured the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, AL. This amazing (but very sobering) museum covers the African-American experience in the US, from slavery to mass incarceration. The MNAAHC not only covers slavery but also looks to the future. The museum also dedicates a large section to African-American legends in music, sports, and other fields.

The 350,000-square-foot museum (the newest in the Smithsonian system) opened to much fanfare in 2016. From the outside, the building looks like three copper-colored, upside-down trapezoids stacked into a five-story structure. However, there are ten stories, five above and five below the ground. Sweet Home Cafe is one of the best of the Smithsonian Museum restaurants, and provides southern favorites such as fried chicken, collard greens, mac and cheese, and sweet tea on Concourse 3.

Concourse Galleries

The large exhibit detailing the African-American experience in the United States remains the biggest draw to the museum. Encompassing three below-ground floors, guests learn the history of slavery, segregation, and civil rights.

Concourse Level Three covers the period from 1400 to 1877. Artifacts tell the story of slavery, including the Middle Passage, dangerous boat conditions, and even the shifting attitude between white indentured servants and black slaves. Placards display numerical facts that are hard to fathom. For example, boats to the Chesapeake carried 42,200 slaves in 1725. By 1775, the number had almost tripled to 127,200.

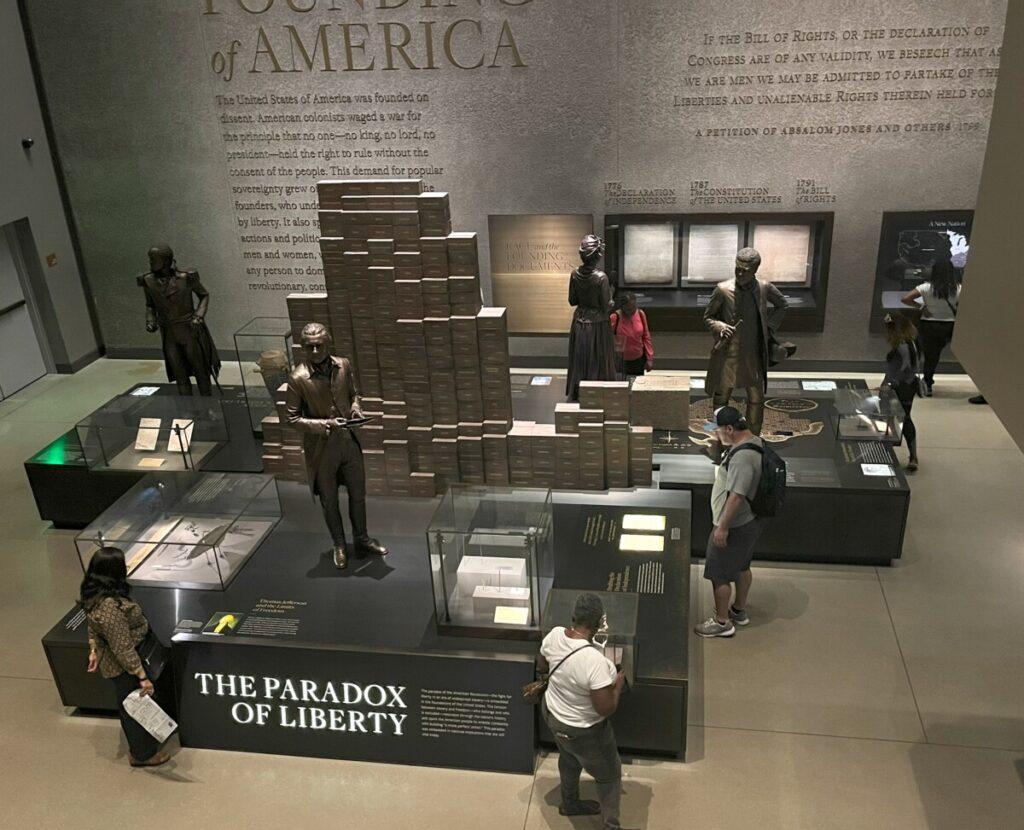

The Paradox of Liberty is a sculpture of Thomas Jefferson standing in front of a wall of bricks listing all the slaves (over 600) he owned. As the writer of the Declaration of Independence, he called for freedom from England but didn’t include any freedom for slaves. Statues of abolitionists Elizabeth Freeman, Benjamin Bannekar, and Phillis Wheatley stand in the background.

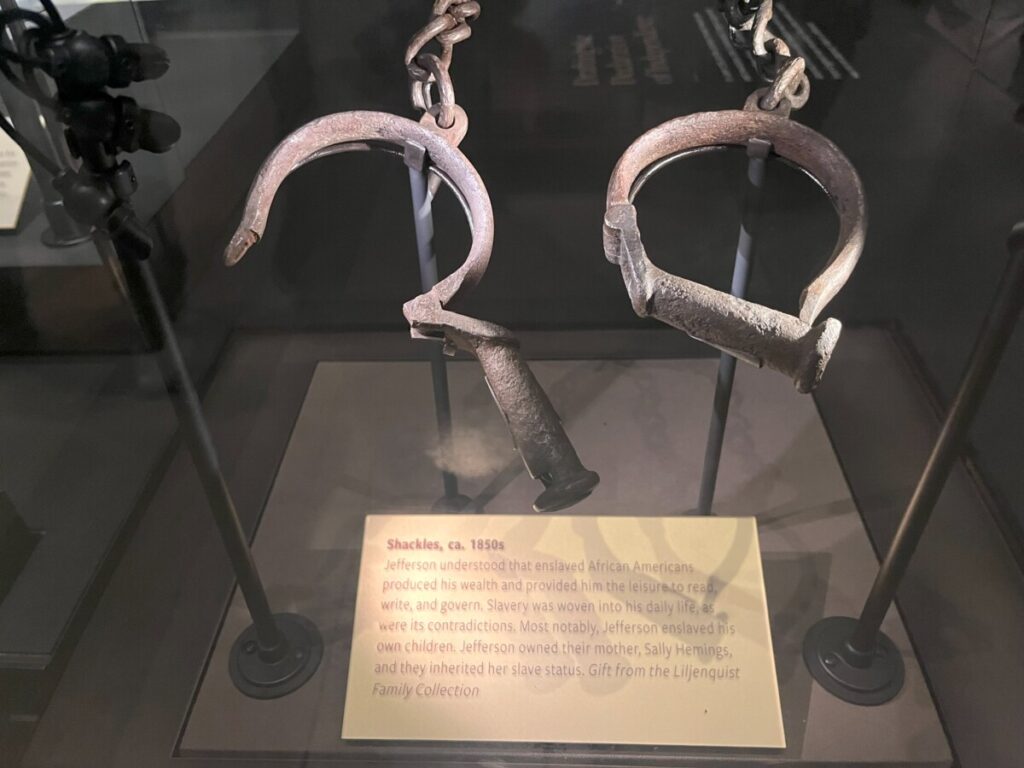

A large cotton bale bearing the name King Cotton proclaims the shift from sugar to cotton as the main driver of the slave industry in the 1800s. A pair of shackles, a personal Bible, a violin used for gatherings, and other personal effects detail this period. We saw numerous bills of sale for slaves and artistic renderings of the auction block and walked inside an original slave cabin from Edisto Island.

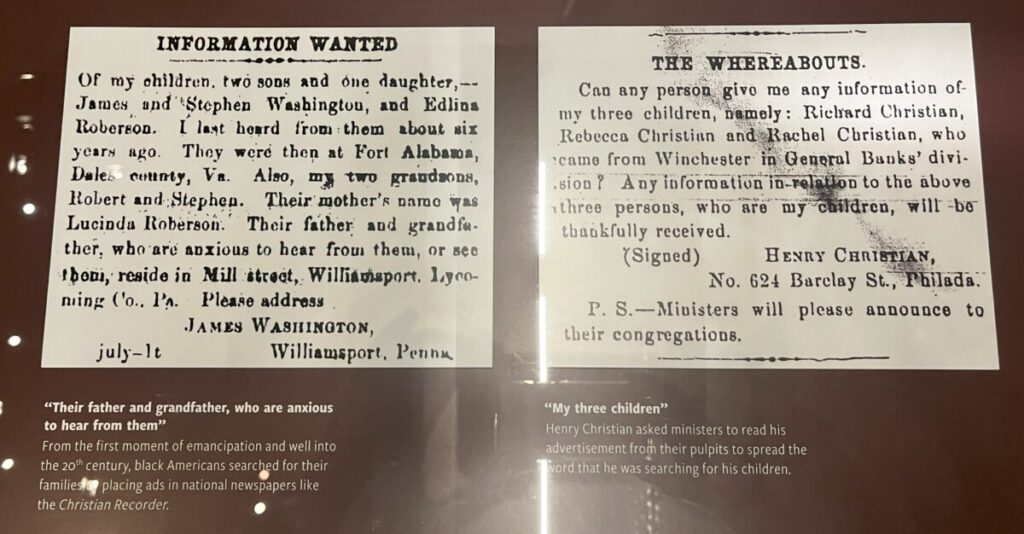

As the Civil War heats up, Frederick Douglass meets with Abraham Lincoln, and the Emancipation Proclamation is signed. The museum highlights famous women such as Harriett Tubman, Charlotte Forten, and Susie King Taylor during the period. After the Civil War, Reconstruction begins, and while some African Americans seek and win elected offices, other former slaves desperately try to locate family members through newspaper ads.

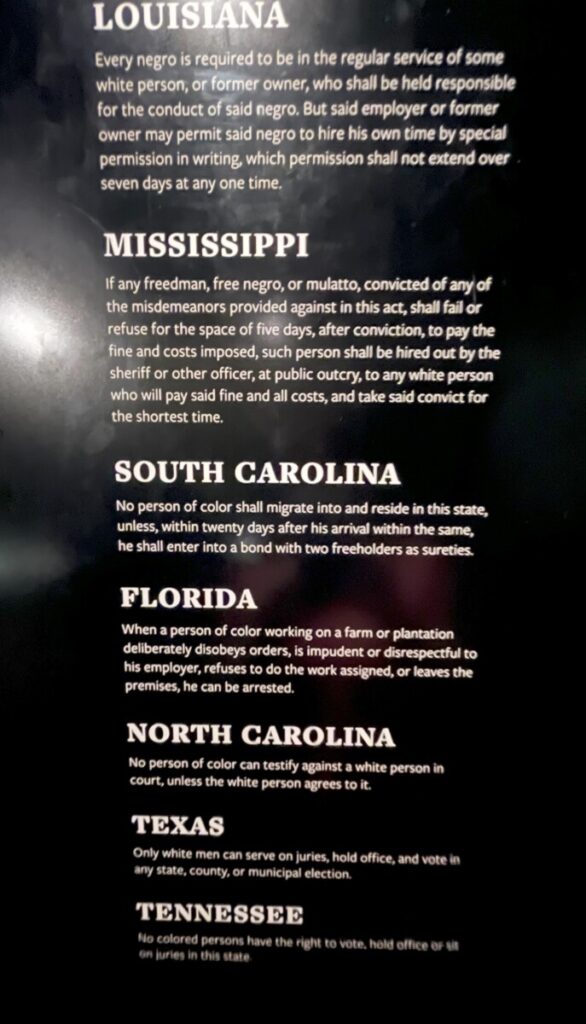

A ramp leads to Concourse 2, which covers 1876-1968. Formerly enslaved people looked forward to enjoying the same freedoms as white people, including land ownership. Several African-American communities sprang up, including Nicodemus, Kansas, and Eatonville, Florida, each with its own school, church, and government. Yet, most of the South followed the Black Codes, a ridiculous set of laws that varied from state to state.

After Plessy vs Ferguson, “Separate but Equal” ruled the day. The museum shows how separate wasn’t equal. We saw examples of the differences in water fountains, bathrooms, and schools. We even walked through a segregated railway car and saw signs saying “Whites only.” As I read some of these posters, I overheard the woman beside me talking to her companion. She said, “I remember those days. I was about nine years old and we could only see the white dentist on Saturdays and we had to use the back door.”

Because many African Americans couldn’t afford to buy land, they signed labor contracts to work and grow crops on a white person’s land for little money. It sounds almost as bad as being a slave since the sharecroppers were always beholden to the landowner. Also, the laws allowed African Americans to be arrested for minor offenses such as vagrancy. Many were transported to convict labor camps and chain gangs. Angola Prison began under the convict lease system and still exists today. We walked under a replica of the guard tower at Angola.

The museum took us through the Great Migration as African Americans sought more welcoming environments outside the South. However, race riots, reports of lynchings, and other atrocities continued all over the US. One section is dedicated to Emmet Till, a young teen lynched in Mississippi in 1955. Leaders such as Congressman Robert Smalls, W.E.B. DuBose, Ida Wells, and Martin Luther King, Jr. fought for more equitable treatment. The exhibition floor culminates with the signing of the Civil Rights Bill.

The next floor of the exhibit covers the modern era from 1968 to the present. We walked briefly through these exhibits as we still had more to see in the museum. Highlights include the Black Power Movement, the Million Man March, and Barack Obama’s inauguration.

Community Galleries – Level 3

All the floors from the Main Level and up offered bright sunlight through the glass windows. Maybe this was deliberate – a way to bring hope and highlight the achievements of African Americans in the United States. We bypassed the theatre on the Main Level and educational classrooms and Library on Level 2 to explore the Community Galleries on Level 3.

The museum was set to close in 45 minutes, so we quickly explored “Sports: Leveling the Playing Field,” which covers significant themes such as slavery, breaking gender barriers, and activism – all within the sports arena. For many, sports scholarships to colleges were the only way to get out of their neighborhoods and rise above poverty. We learned about African-American strides in various sports such as baseball, basketball, and track and field. A large section is dedicated to Muhammad Ali. There are stories from significant athletes such as Jackie Robinson.

Athletes also discovered ways to fight for equal rights. Wilma Rudolf fought for change after winning numerous track and field medals at the 1956 and 1960 Olympics. When her hometown in Tennessee wanted to honor her with a banquet and parade, she refused to attend because it was segregated. City leaders relented, and the parade and banquet became the first integrated event in the town’s history.

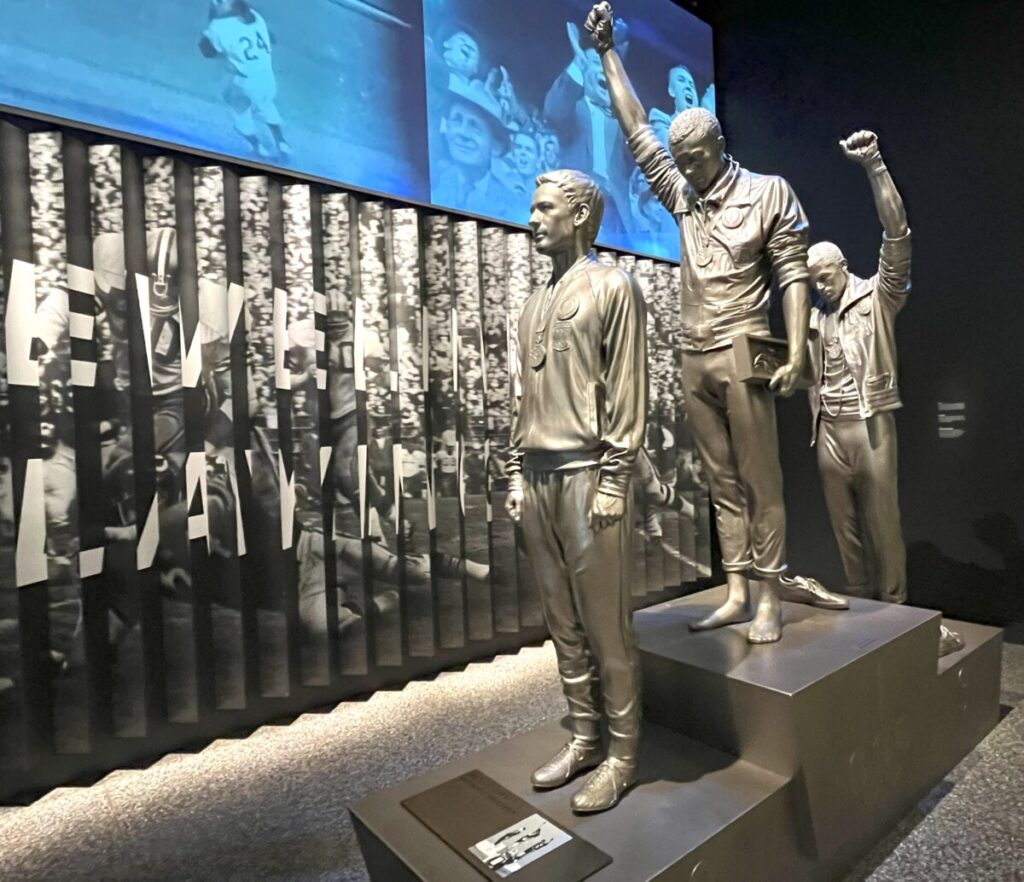

The exhibit features a statue of three athletes from the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. Gold medalist Tommie Smith and Bronze medalist John Carlos gave the Black Power Salute with gloved hands and heads bowed during the award ceremony on the podium. Both wore black socks without shoes to symbolize African American poverty, and Carlos wore a beaded necklace to honor those lynched. The silent protest brought stiff repercussions. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) suspended both athletes from the US team. The media criticized the action and neither returned to the 1972 Olympics.

Other exhibits on this flow showcase African Americans in the military and the power of place. Making the Way Out of No Way shows how African Americans created their own educational institutions, including Wilberforce University and the Homer G. Phillips School of Nursing, fraternities and sororities, relief organizations, and churches.

Culture Galleries – Level 4

Chuck Berry’s red Cadillac El Dorado greeted us on the fourth floor at the beginning of the Musical Crossroads Exhibits. Memorabilia included guitars, costumes, and the history of some of the best-known African-American musicians. From Lead Belly and Marion Anderson to the Ronettes and Prince, the exhibit offers a fascinating glimpse into the African-American experience in the music industry.

Taking the Stage focuses on African-American entertainers. Cases display clothing from pioneer TV shows such as Julia, The Jeffersons, and Good Times. We learned how the advent of record albums and later television allowed comedy performers such as Redd Foxx, Richard Pryor, and Bill Cosby to break out of segregated nightclubs on the “Chitlin’ Circuit.”

The Cultural Expressions exhibit details the food, fashion, gestures, and traditions handed down through the generations. African designers are highlighted with decorative ironworks from Phillips Simmons, sawgrass baskets from Mary Jackson, and an Hermes scarf by Kermit Oliver.

In Conclusion

The subject matter in this museum is so broad that you can’t take it all in at once. I recommend visiting over two days, which is possible since tickets are free. I’d love to return and focus solely on the Community and Culture Galleries on the upper levels since we went by them too fast to absorb everything. We also missed several exhibits and the Contemplation Court completely.

Plan to spend 2-3 hours at the museum and eat at Sweet Home Cafe. For more information, visit the website here.

Pingback: Niagara Falls and Finger Lakes of New York Itinerary • Finding Family Adventures