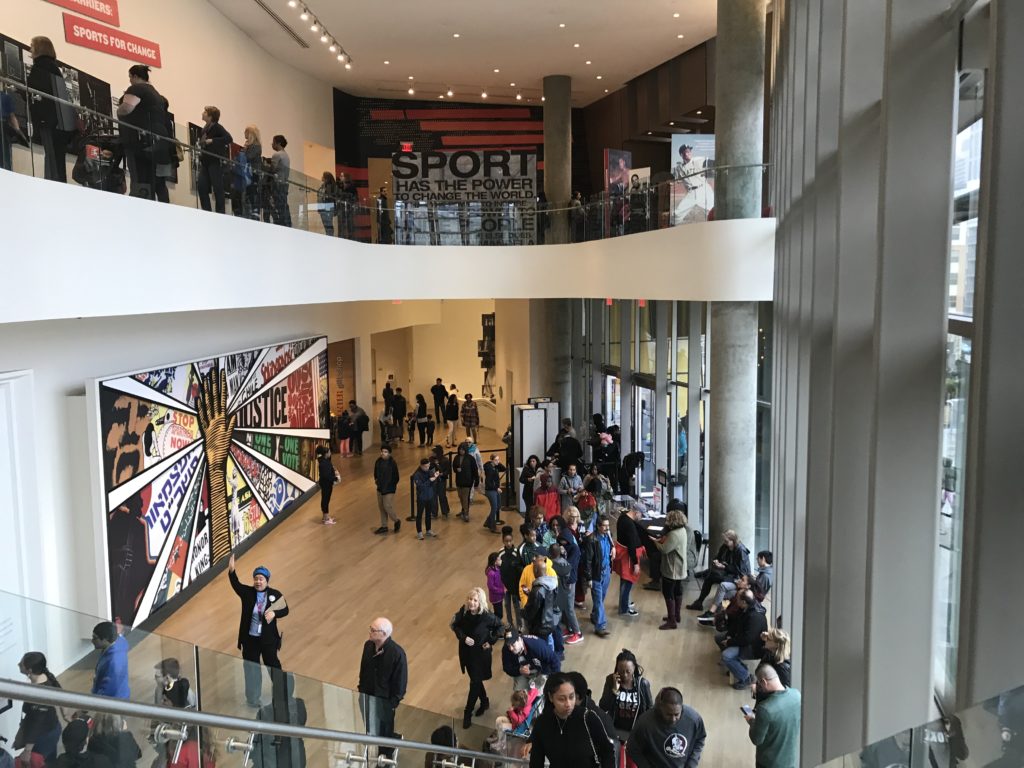

Opened in 2014, the National Center for Civil & Human Rights is one of Atlanta’s newest museums. In response to Pepsi sponsoring Super Bowl LIII right here in Coca-Cola’s home city, the Coca-Cola Foundation gave a $1 million grant providing free admission to the museum for the entire month of February. Not just Super Bowl weekend. Not just for visitors to Atlanta. It’s for everyone for the entire month.

Visitors enter on the second floor of the museum after going through a security checkpoint. Typically, they explore the second floor civil rights exhibit, then follow upstairs to the human rights exhibit. Because larger than average crowds, museum staff told us to start either on the first or third floors.

Third Floor – The Global Human Rights Movement

At the beginning of this exhibit, the staff member suggest we click on the interactive hologram to hear different stories from those who lost their human rights. A woman from the Ukraine told her story about losing her family to the Holocaust.

On one wall were the defenders of human rights. Some were typical like Gandhi, MLK, but some I’d never heard of such as Estela Barnes de Carlotto from Argentina. During the “Dirty War,” right wing factions kidnapped those with liberal views. Many pregnant captives were killed shortly after their child’s birth. Upon her daughter’s murder in 1977, Estela joined Las Abuelas to find her grandchild. To date 114 missing babies, including her grandson, have been found.

On the opposite wall were the offenders of human rights: including Pol Pot, Baby Doc and Hitler. In the middle of the room stood placards of those instrumental in women’s rights, immigrants’ rights, and LGBT rights.

Addressing issues such as human trafficking, the center encourages visitors to think about what they can do to help. Production by slave or child labor of soccer balls, palm oil, flowers, tennis shoes and chocolate often violate human rights. For example, a majority of cacao beans (found in chocolate) come from West Africa. Often children and slaves provide labor for cacao plantations. Purchasing only fair-trade chocolate is a way to help.

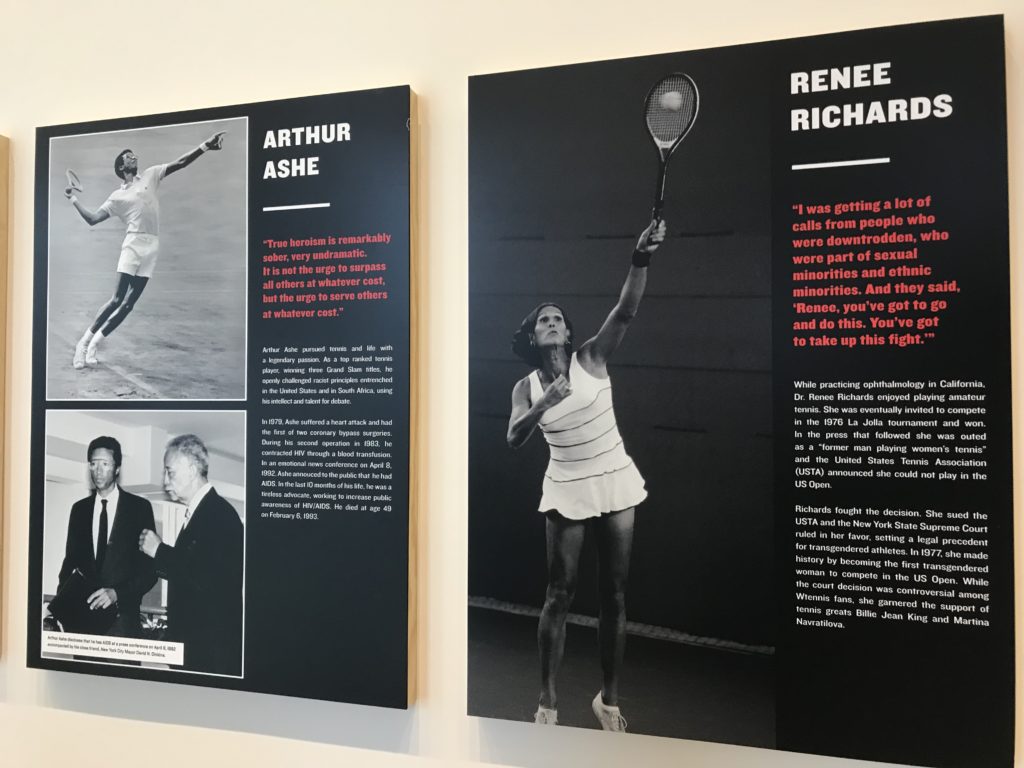

We then saw the temporary exhibit called “Breaking Barriers: Sport for Change.” It focused on athletes who used their status to fight for human rights: athletes such as Muhammad Ali, Billie Jean King and Jesse Owens. I learned about US runners, Tommie Smith and John Carlos who at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, raised their black-gloved fist in a salute while on the podium. Smith said it was “a human rights salute.” Regardless, the IOC expelled them. Back in the US, they faced criticism and death threats.

Second Floor – The American Civil Rights Movement

TV sets showed footage from politicians declaring their views on segregation. I couldn’t believe what I heard. Enough to make my blood boil, I felt thankful that I wasn’t around during that time.

On one wall, a history of Atlanta’s Sweet Auburn neighborhood showed key events and a timeline. In the middle, displays explained various events happening all over the south. Did you know that Rosa Parks wasn’t the first African-American refuse her bus seat in Montgomery? That title belongs to Claudette Colvin, a 15-year-old student who didn’t give her seat to a white person earlier in 1955.

The center highlighted lunch counter sit-ins. An exhibit simulated what it felt like to be at a lunch counter in the 1960s. Because of the long line, we skipped this but I heard it was powerful.

Next, we saw a school bus with mug shots of Freedom Riders. We lifted the handsets to hear some of the participants recall their experiences. I listened to a man named Bernard Lafayette. Although beaten badly, he later became a Theologian at Emory University. Inside the “bus” were videos of arrests during the Freedom Rides. On the opposite wall, films showed Birmingham’s Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor and the police’s use of fire hydrants and attack dogs during demonstrations. Back to Atlanta’s history, plaques detailed the response of some of Atlanta’s business leaders including William B. Hartsfield and Ivan Allen. Even Rich’s department ended segregation when the public schools did. Before that time, African-American customers could purchase clothes, but weren’t allowed to try them on. Additionally, the Magnolia Room at the department store served only white customers.

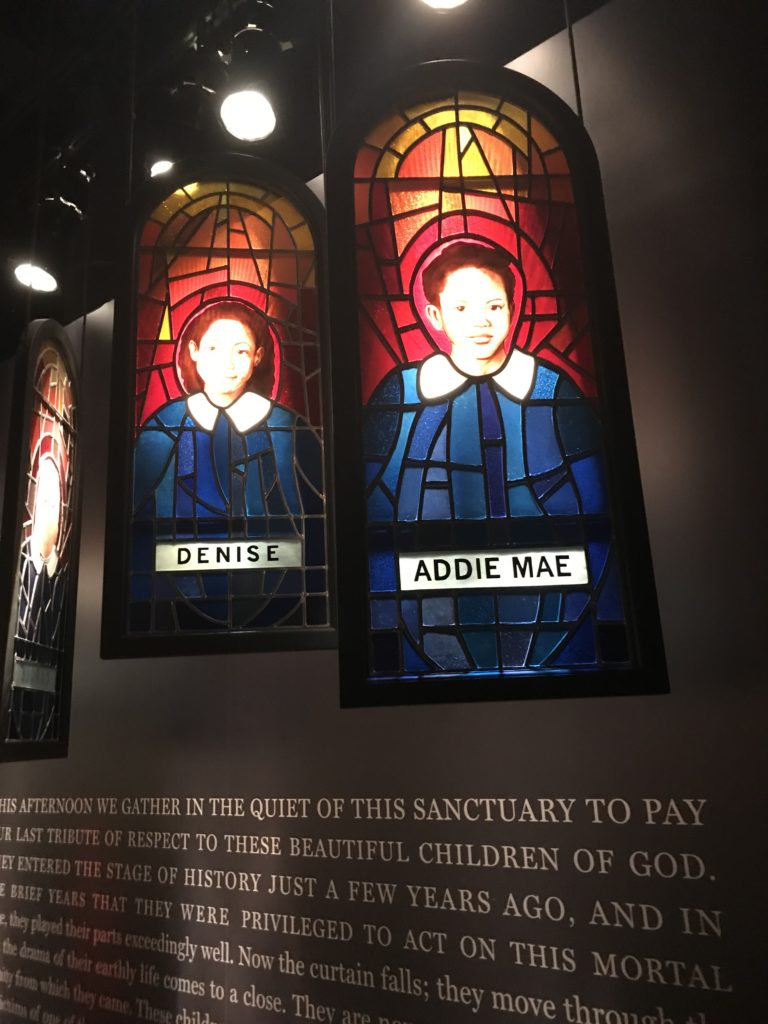

A large room, dedicated to MLK Jr.’s March on Washington in 1963, showed who helped organize it and the logistics involved. Another room detailed some of the murders associated with the movement. In 1963, a bomb killed four young girls at 16th Street Baptist Church. Freedom Riders, Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodwin and James Chaney were murdered in Mississippi. In 1965, Selma policemen beat unarmed protesters who were trying to march to the state capitol in Selma. It is referred to Bloody Sunday.

The last section details the assassination of MLK Jr. at the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis with films of Walter Cronkite and Bobby Kennedy announcing King’s death. Pictures show the 3-mile funeral procession from Ebenezer Baptist Church to Morehouse College. The exhibit lead up to the 3rd floor to a room showing people who died during the civil rights movement. On one side is a picture, while the other shows what happened.

First Floor – Morehouse College Archives

On the bottom level, Morehouse College features a rotating exhibit of MLK Jr.’s letters and papers. The last glass case shows items he had with him in Memphis. He carried shaving powder, talcum powder, a black comb and a couple of prescriptions.

For more information about the center, click here.