Castillo de San Marcos in the historic part of St. Augustine remains a top tourist spot. However, many don’t know about St. Augustine’s other fort, sometimes called the “back door of St. Augustine,” Fort Matanzas.

For starters, Fort Matanzas is harder to reach. Located about fifteen miles south of St. Augustine on Anastasia Island, visitors must take a five-minute ferry ride to see the coquina watchtower. Purchasing tickets online isn’t an option either as the National Park Service distributes them on a first-come, first-serve basis. However, with fewer tourists, a visit to Fort Matanzas provides an enjoyable experience.

Visitor Center

When you turn into the parking lot, go first to the Visitor Center. Walk through the open archway and the ferry ticket window appears on the right. Since the ferry only holds 24 people, spots book up quickly. Once you get your free ferry tickets, you can plan the activities accordingly.

The free round-trip ferry ride and tour of the fort takes about 45-50 minutes. Park rangers ask you to gather at the dock about 10 minutes before the departure time. Ferries leave on the half-hour every hour 9:30 am to 3:30 pm, excluding the lunch hour Wednesday through Sunday. Currently, ferries don’t run Monday – Tuesday.

Nature Trails

Since we had over an hour to spend before our 11:30 am ferry, the ranger suggested we take a guided walk beginning at 10:30 am. Before it started, however, I noticed a sign next to the restrooms pointing to a nature trail.

The 0.5-mile loop trail featured boardwalks flanked by lush plants in the maritime forest, also called the coastal hammock. Live Oaks provided lots of shade on the walkways. About halfway, the view opened onto the Matanzas River and sand dunes.

A plaque explained the name Matanzas is Spanish for “slaughter.” About the same time the Spanish landed in St. Augustine, French Huguenots built Fort Caroline near Jacksonville. Conflicts between the two groups came to a head in 1565 when the French settlers attacked St. Augustine. However, storms scattered the French ships, leading to their defeat. At this particular point, the Spanish found survivors of one of the French ships that sank. According to the NPS, the Spanish saved some people, but overall 250 died.

We met up with the ranger who was leading a walk on the north side of the visitor center. This estuary of marsh grasses looked very different than the boardwalk trail. Walking north, the land on the eastern side of the trail (nearest the Atlantic Ocean) “floods” about twice a day when the tides roll in. All the vegetation has to survive with lots of water. On the higher, western side of the trail, Youpon Holly produces bright red berries while salt-tolerant Spanish Bayonet generates sharp-pointed leaves that can draw blood. Mangroves and palmetto trees also grew in the area.

As we walked further, he told us to look for crabs creating shadows on the trail. I didn’t see any crabs, but definitely holes where they dug looking for food. The ranger also pointed out the trees that looked windswept. Because the winds carry salt in the air, they kill the front part of the trees. At the end of the trail, we came to views of the Matanzas River, Fort Matanzas, and the 200-acre Rattlesnake Island on which it resides. While the walk was short – just 100 feet – we found the ranger’s explanation of the grasses, trees, and plants fascinating.

The Fort

We boarded the ferry for the five-minute ride across the river. In the distance, dolphins flipped high above the waves. At the fort, a different park ranger gave us a brief history.

Fort Matanzas was built between 1740-1742 as tensions between England and Spain necessitated stronger fortifications for St. Augustine. In 1741, the British ship, St. Philip, fired on a Spanish sloop, killing two soldiers. As the fort was nearing completion in September, the soldiers at Fort Matanzas fired cannons at two British longboats. Although the cannon fire missed the boats, the British scurried away.

The fort, built from coquina just like Castillo de San Marcos, protected St. Augustine’s back door – the Matanzas Inlet. It ceased operations when the US Government took over Florida in 1821. Throughout the years, extensive renovations have strengthened the walls, not for sentries, but for tourists.

Inside the Fort

Much smaller than Castillo de San Marcos, Fort Matanzas housed only seven to ten men at a time. Because it was hard to reach, the soldiers stayed for a month at a time.

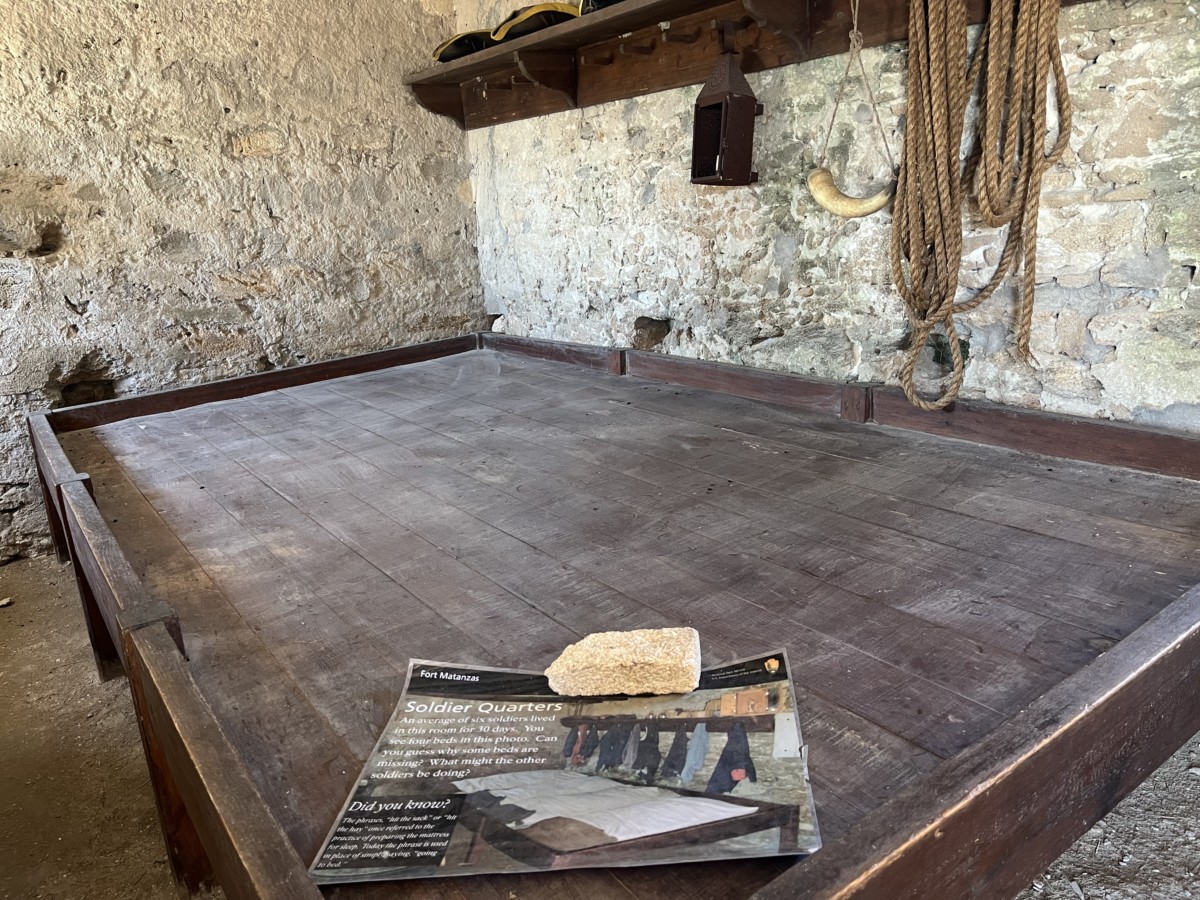

Inside the fort, we saw the soldiers’ quarters off of the gundeck. A large fireplace provided heat for the men and for cooking. On the other side of the room, a wooden slat originally held four beds for the soldiers. Upstairs the officer’s quarters featured arched walls and the entrance to the powder magazine. From this level, a ladder led to a large rooftop lookout deck. The soldiers must have been thin because tourists with camera bags could barely squeeze through the openings!

Outside, five cannons protected the fort. With a range of a half-mile, they could reach the inlet. Today, only two of the original cannons, mounted in 1793, sit on the gundeck. The park service uses two replicas for firing demonstrations.

Beginning around 1796, the fort needed various repairs including new wooden stairs, a cistern pump, and a roof. In 1820, lightning caused catastrophic damage to the structure and when the US took over Florida in 1821, they deemed it useless. At some point, the sentry tower fell off of the fort. For almost 100 years, the fort continued to deteriorate until Congress approved funds in 1916 to make necessary repairs.

Although smaller than Castillo de San Marcos, Fort Matanzas begs a visit. Tourists enjoy watching dolphins in the river, as well as seeing the changes to Rattlesnake Island. When Fort Matanzas was built, Rattlesnake Island encompassed two acres. Upon completion of the Intracoastal Waterway, Rattlesnake Island has over 200 acres.

For more information about Fort Matanzas, click here.