Until a few years ago, no memorial paid tribute to the over 4,400 known victims of lynching in the United States. Bryan Stevenson, of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) sought to change that. In 2018, the EJI opened both the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration.

This post focuses on the second part of the complex – the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. However, you can read the previous post about The Legacy Museum, just two miles away. Serving as the first Capital of the Confederacy and having the second largest slave population, Montgomery presents an appropriate location for both the musuem and memorial.

Included in the Legacy Museum’s $5 ticket price, complimentary shuttle buses transport guests to and from the memorial. Or, people wanting to only see the memorial can go there separately and pay the $2.50 admission fee.

Across the street lies the National Center for Peace and Justice, which is free. The center features a wall of soil jars collected from lynching sites, similar to the one inside the Legacy Museum.

The Grounds

Set on six acres with a view of downtown, the site looks more like a nice park – until you look at the subject matter – the brutal lynchings that went unpunished for decades.

But because of the park-like landscaping, one can’t help but want to spend time here. That’s the memorial’s purpose – to cause visitors to spend time reflecting, remembering, and honoring lynching victims.

The Memorial

At the top of the hill, visitors walk to a square-shaped open pavillion. Hanging from the ceiling, over 800 weathered steel blocks, each representing a county in the US, lists the names and dates of lynching victims.

Walking along, the ceiling stays the same height but the floor slopes down a ramp at each turn. Soon, visitors can’t read the names. However, plaques on the side of the wall detail some of the injustices. “William Lewis was lynched in Tullahoma, Tennessee in 1891 for being ‘intoxicated’.” “Seven black people were lynched near Screamer, Alabama, in 1888 for drinking from a white man’s well.” “Dozens of black sugar cane workers were lynched in Thibodeaux, Louisiana, in 1887 for striking to protest low wages.”

At the last turn, the memorial culminates with a water wall with seating for reflection. A quote reads, “Thousands of African Americans are unknown victims of racial terror lynchings whose deaths cannot be documented, many whose names will never be known. They are all honored here.”

Each name represents a life and a story. But more than that, each person listed had family and friends affected by their death. Those deaths affected descendants of family members as well. Just watch some of the videos here.

Many kids remember getting in trouble at home and hearing their mother say, “Wait until your father hears about this…” That phrase struck fear and dread into many a child. That’s how lynchings were. Living in the fear that one misstep could kill you or a loved one caused terror and permanent psychological scars. Watch the EJI video from Fred Croft’s family here.

Monument Park

After exiting the pavilion, the monument park section lies on the back part of the property. Alphabetized by state, the second set of tomb-like blocks lies prone so that visitors can read the victims’ names.

Although I expected the list of victims to be high in certain areas such as Alabama and Mississippi, I felt quite disheartened when I looked at Northwest Louisiana where I grew up. Two columns of names for both Caddo and Bossier Parishes were etched into the rusted steel.

Sculptures

From this point, a sidewalk winds down the hill passing several poignant sculptures. The premise of the EJI is that slavery didn’t end; it evolved. Over the years, slavery transformed into lynchings, segregation, and now into mass incarceration.

The sculpture “Raise Up” with 10 Black men encased in concrete raising their hands depicts police violence in the past few years. Sculptress Dana King recognizes the silent, but strong women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in “Guided by Justice” which shows three women in various stages of life. The Memorial Grove honors Ida B. Wells, a Black female activist who exposed lynchings to foreign audiences.

Lynching Memorial Project

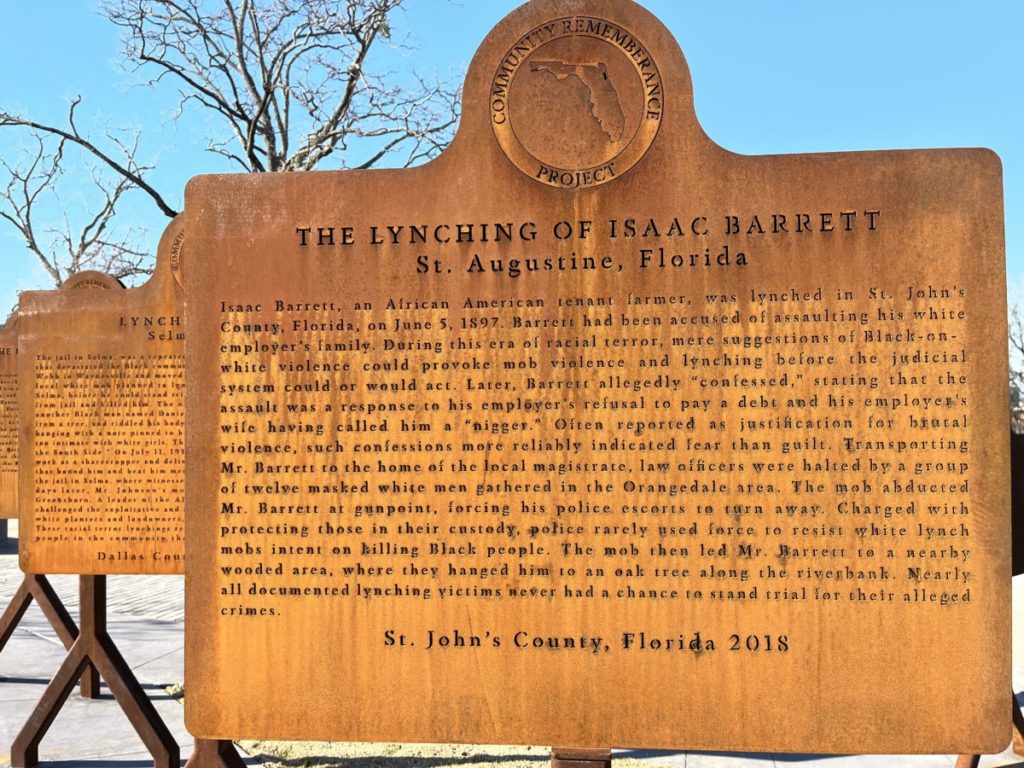

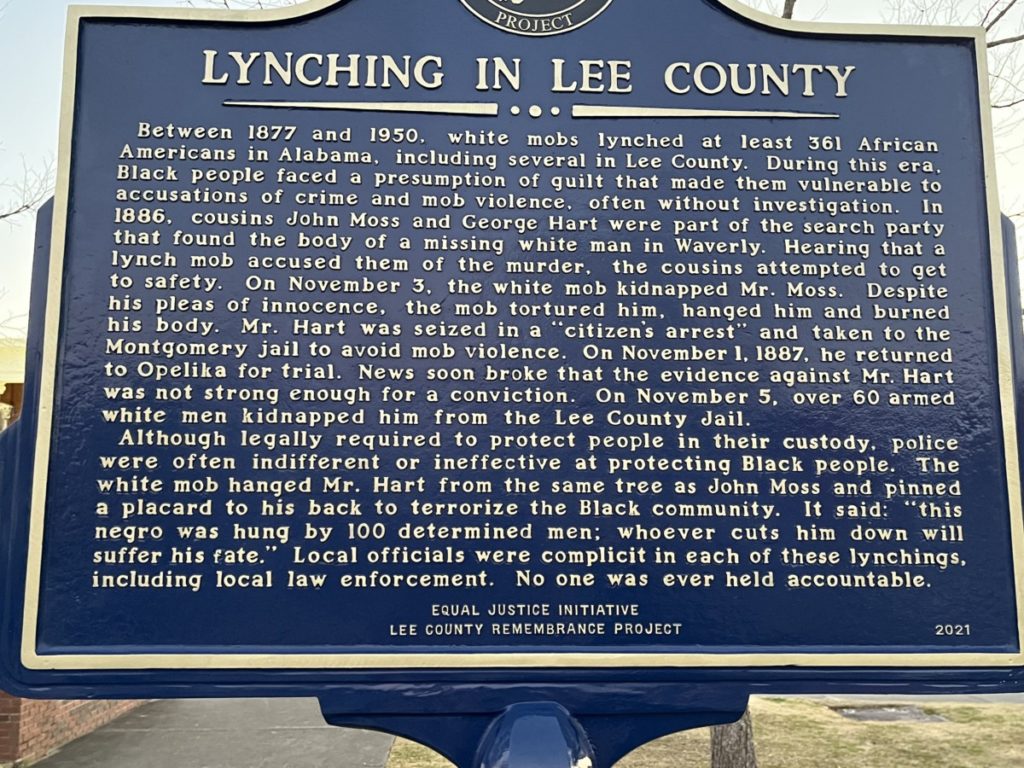

The EJI is involved with the Lynching Marker Project. By placing historical markers at the sites of documented lynchings around the country, history won’t be erased. A grouping of these markers, formed in a triangle shape, stands on the grounds.

Later that day, I stopped in Opelika, Alabama. In front of the Lee County Courthouse, one of these plaques stood erect.

Conclusion

Plan to spend anywhere from 30 minutes to 90 minutes at the site.

To learn more about lynching, see the EJI Report Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror that led to the creation of the memorial. For information about hours, tickets, and location, visit the website here.